VIRTUAL EXHIBITION

donald e. camp: Dust Shaped Hearts

This virtual exhibition is based on Donald E. Camp’s Dust Shaped Hearts series.

Essay by Amie Potsic, CEO & Principal Curator, Amie Potsic Art Advisory, LLC

Donald E. Camp

Donald E. Camp has a strong reputation in Philadelphia with his work featured in museum collections and exhibitions in a number of respected institutions there and across the United States. In 1995, Camp was awarded an Individual Artist Fellowship by the prestigious Pew Center for Arts and Heritage solidifying his reputation among scholars, critics, and patrons. He went on that same year to garner awards from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. With these endorsements of his work by some of the most important funders in the artistic community, Camp developed his signature work further to expand Dust Shaped Hearts, for which he has become known. Because Camp is a renowned artist and photographer, his work is appreciated and collected by patrons, critics, and institutions interested in photography, contemporary art, and African American artists. He is currently a Professor Emeritus at Ursinus College, where he had been an Artist in Residence for over 10 years and where there is a photography collection in his name.

Significance and Impact

Donald E. Camp’s signature series, Dust Shaped Hearts, has garnered numerous awards and brought him an invitation to include his oral history in The History Makers, the Nation’s Largest African American Video Oral History Collection. Dust Shaped Hearts was started by Camp early in his artistic career but later in his photographic career, having been a successful photo-journalist for nine-years before going to Temple University for his BFA and Tyler School of Art for his MFA. Coming from a background in newspaper photography, Camp created Dust Shaped Hearts in response to the mug shots of African-American men he consistently saw published as well as the popular notion in political conversation of an impending extinction of the African-American male. Camp created the series to challenge stereotypes and historical limitations while honoring and memorializing African-American men of character.

The series was very timely and commented on the current discussion of multi-culturalism, racism, and civil rights prevalent in the political conversation happening in America in the 1990’s. It also operated within Post-Modernism’s penchant for political commentary and photography’s evolution towards the large-scale and conceptual. Camp’s work was part of a larger group of African-American artists making social commentary on racism in the 1990’s such as Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson, and Kara Walker. Camp’s work was also strongly influenced by the Blues and Jazz, genres whose musical styles communicated a depth of emotions and introduced rhythm and improvisation to the artist’s printing process.

Dust Shaped Hearts has grown to include women as well as people of a variety of backgrounds to acknowledge Camp’s belief that the struggle against ignorance and intolerance is a universal one. His work continues to comment on racism in American culture today as his work Emmet Till / America (created in 1989 and recently exhibited in 2018) references the historically significant photograph of Emmet Till. Emmet Till’s brutal experience and its portrayal were formative elements in Camp’s life and poignantly inform his work. Camp’s artwork also currently exists in conversation with artists discussing race-relations and the complexity of inclusive histories such as Kerry James Marshall and Nick Cave. Dust Shaped Hearts continues as Camp produces new works and lends his voice to the artistic dialogue on racism and human rights today.

Camp created Dust Shaped Hearts using a unique photographic process he formulated himself. In an effort to immortalize the faces of the subjects he photographed, he forged and refined a biological, chemical, and metaphysical process of creating photographic prints from casein and earth pigments. Insightful works uniquely created to stand the test of time, Donald E. Camp’s oeuvre addresses the universal human struggle against intolerance and stereotype. Melding the subject matter of the human face with a lyrical and organic printing process yields a body of work that investigates beauty, history, and humanity. Camp’s influence is strongly felt in the Philadelphia artistic community and exists in dialogue with national and international discussions on race. As such, the relevance and significance of his work is formidable, growing as the series expands to honor additional compelling subjects and receive recognition.

DUST SHAPED HEARTS

© Donald E. Camp, The Man Who Sews - Collin Louis, 2008, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | Collection of the Michener Art Museum.

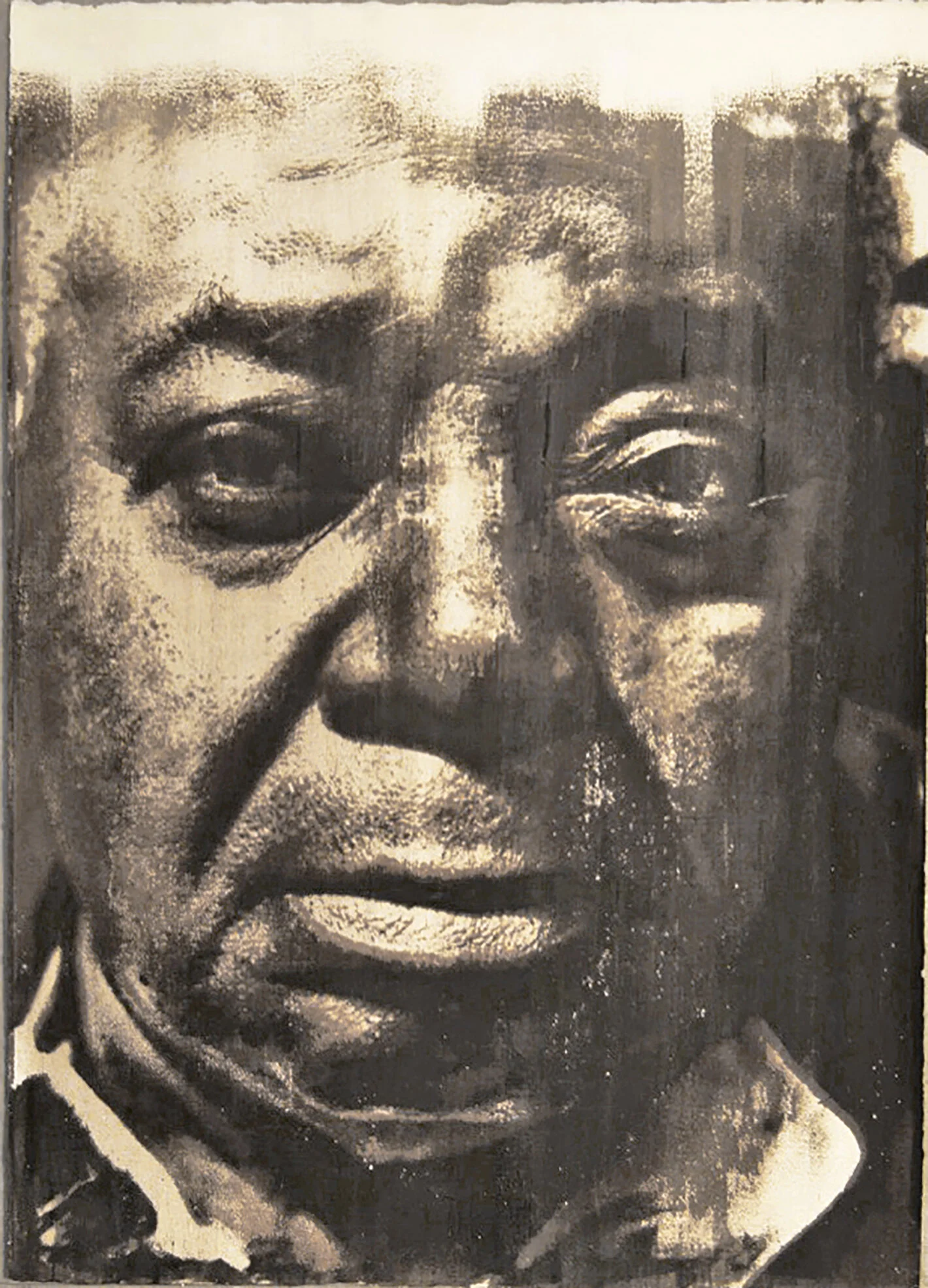

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Paints – Mr. James Brantley, 1995, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, The Teacher – John Dowell, 2015, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | Collection of the Delaware Art Museum.

© Donald E. Camp, Woman Who Writes – Ms. Lorene Carey, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | Collection of the Free Library of Philadelphia.

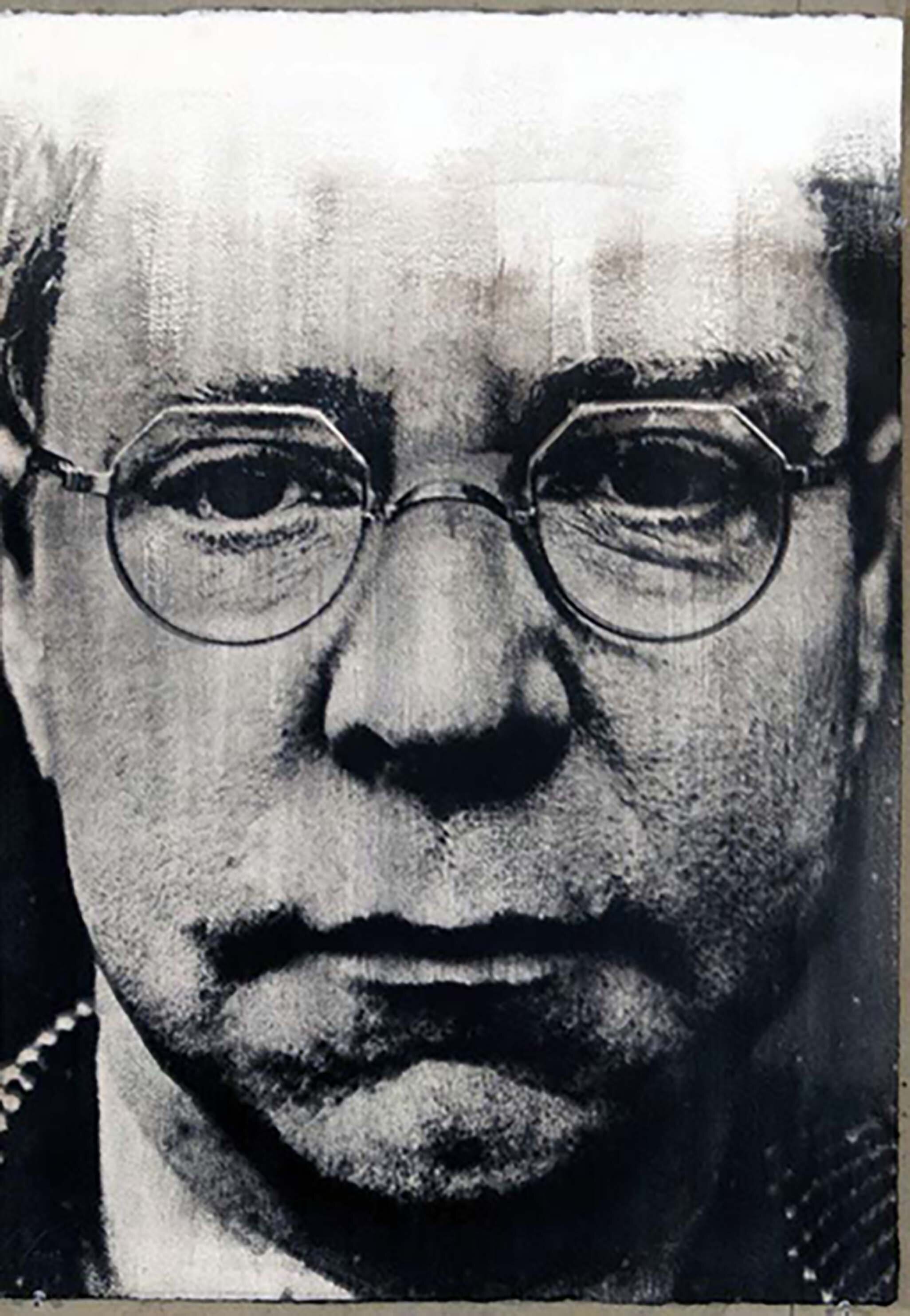

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Writes - Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., 1992, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

© Donald E. Camp, Father-in-Blues/ Jimmy “T99” Nelson, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Brother Who Taught Me to Dance/ Ira Camp (from Sons of My Father suite), 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | Collection of the Pennsylvania Convention Center.

© Donald E. Camp, Brother Who Taught Me to See – Mr. Herbert Camp, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Hears Music – Mr. Rufus Harley, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Feels Shape/ David Stevens, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment print on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | Petrucci Family Foundation Collection of African American Art.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Hears Music – Mr. Andre Raphael Smith, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Sees/ Louis Massiah, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Writes/ David Bradley, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | Collection of the Delaware Art Museum.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Sees Light - Mr. Will Larson, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | Donald E. Camp Collection at the Berman Museum, Ursinus College.

© Donald E. Camp, The Historian - Dr. John Hope Franklin, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Photographer – Ms. Jackie Brennan, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 42 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Writes/ Marc Crawford, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | Private Collection.

© Donald E. Camp, The Magician – Mr. Chris Capehart, 1996, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Is A Father, 1994, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Self, 2010, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 42 x 30 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Winifred Lutz - Woman Who Searches, 2012, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Woman Who Cooks - Chef Leah Chase, 2007, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Congressman John Lewis, 2015, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | Collection of the Michener Art Museum.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Sees Magic – Francis Menoti, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 22 x 30 inches. | Private Collection

© Donald E. Camp, Woman Who Paints – Ms. Alice Oh, 2012, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Dr. William Roberts, 1992, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 22 inches. | Collection of Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Sings Blues - Mr. Willie King, 2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, The Drawer – Mr. Earnest Brown, 2008, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Woman Who Finds Word's Meaning – Dr. Nzadi Keita, 2012, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Man – Mr. John Daniels, 2008, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, The Magician - Teller, 2003-2006, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Silver Cowboy – Mr. Jacob Gassenberger, 2008, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprint, 30 x 40 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Young Man #2 – Million Man March, 1996, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprints, 41 x 29 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Willow, 2008, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprints, 41 x 29 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

© Donald E. Camp, Young Man #3 – Million Man March,1996, Casein and raw earth pigment on archival rag paper, Photographic Casein Monoprints, 41 x 29 inches. | For all sales inquiries or commissions contact Amie Potsic Art Advisory.

Donald E. Camp: Artist Statement

Through insightful prints uniquely created to stand the test of time, Dust Shaped Hearts addresses the universal human struggle against intolerance and stereotype. Melding the subject matter of the human face with a lyrical and organic printing process yields a body of work that investigates history, humanity, and beauty.

Dust Shaped Hearts, as a series, began in 1993 with the purpose of recording the faces of African American men. The project was intended to be a sardonic statement about news reports of the threatened “extinction of the African American male.” Drawing upon my experience as a photojournalist, I re-defined the “newspaper headshot,” in order to go beyond stereotype and give thoughtful attention and permanence to the men I photographed.

Expanding the scope of these portraits, I photograph the human face (male and female), not because the person possesses a dramatic “photographic” face, but because of the person’s character. I photograph writers, artists, judges, musicians, and others. The face is shaped in the darkroom process as I expose and scrub the prints until they convey an authenticity and power. The scale is large (22 x 30 or 30 x 42 inches) to allow the visual language of the materials to be seen. Due to the specificity of each person and my non-reproducible printing method, only one unique print is made of each subject. Each face demands its own solution.

The existence of the Blues has greatly influenced my choice to create a unique photographic process. After researching light sensitive processes, I chose to modify a 19th century casein and pigment process settling on this form because it is more archival than the standard rare metal prints. Using materials as metaphor for the male and female, Dust Shaped Hearts is printed using earth (pigment) and milk (casein). Combining these organic materials to make images parallels my observation that basic photography is biological, not mechanical. In printing, I try to bring the materials together to make them one: the image, casein, and pigment become paper and the paper becomes pigment, casein, and image. Created in this manner, my work seeks to communicate the honesty and sadness of a great blues performance.

DIGITAL EXHIBITION

© Donald E. Camp, Man Who Writes - Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., 1992, Photographic Casein Monoprint, Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Donald E. Camp's artwork on race and human nobility is currently being presented by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in a digital exhibition of their African American Art Collection. To view the online exhibit: https://www.philamuseum.org/calendar/exhibition/african-american-art-19

ART WATCH PODCAST

Decorus exhibition curated by Amie Potsic. Artwork by Donald E. Camp, Tom Judd and Aubrie Costello. Presented at Space and Company in Philadelphia.

PUBLICATION

URSINUS MAGAZINE

MASTERS OF PHOTOGRAPHY

DELAWARE ART MUSEUM

Emmet Till, America and Me

To learn more: Emmett Till / America 1955, Donald Camp – Delaware Art Museum

DUST SHAPED HEARTS: Photographs by Donald E. Camp

https://www.ursinus.edu/live/profiles/1196-dust-shaped-hearts-photographs-by-donald-e-camp/_ingredients/templates/berman-2018/exhibition

CATALOGUE ESSAY

For Donald E. Camp and Robert Frank’s concurrent exhibitions at The Berman Museum of Art in 2011.

“Finding the Blues: A Photographer’s Quest” by Donald E. Camp, with Amie Potsic

© Donald E. Camp, Emmett Till / America 1955, Glass mirror with liquid light and sun-baked acrylic.

Collection of the Delaware Art Museum.

“The activity of art is based on the fact that a man, receiving through his sense of hearing or sight another man’s expression of feeling, is capable of experiencing the emotion which moved the man who expressed it… And it is upon this capacity of man to receive another man’s expression of feeling and experience those feelings himself, that the activity of art is based........ it is a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings, and indispensable for the life and progress toward well-being of individuals and of humanity.” -Leo Tolstoy, “What Is Art?”

The Beginning

I am an African American male, born in 1940 in western Pennsylvania on the Ohio line. I was raised in a small steel town, the youngest child of seven children, all of whom loved and made art - mainly music. We are the sons and daughter of a barber and a singer, both of whom were admired and despised in the community. My father was an excellent barber, mentor, and business person. My mother was the church choir director and a singer who could, even when I was nine years old, make me stand still and listen intently when she sag Ave Maria. Art and music permeated our household.

My siblings and I learned early that we should not limit our own dreams nor the dreams of others. We were often resented because our dreams were big and went far beyond the steel mill in which we and all other children in the town were expected to work one day. We had the lofty dreams of becoming artists and doctors. Despite our dreams, or because of them, we were often reminded by our parents that we should never look down on anyone or ever allow anyone to look down on us.

My mother died in front of me when I was twelve years old. As my brothers and sisters were older and had already left home, I was raised like an only child by my father with the help of our neighbors. Our town was filled with European immigrants and Southern migrants who had come to work in the steel mills. They came from a place where it was understood that it takes a village to raise a child. The Polish couple that lived across the street made sure I had a daily hot lunch and dinner while the African American and Sicilian couples who lived next door made sure I did my homework and stayed safe. Out of love for my mother and respected for my father, I was nurtured by our international village.

Civil Rights

To keep me out of trouble and teach me a bit about business, I started working in my father’s barbershop after school and on weekends. I learned to cut hair, shined shoes on Sunday mornings, and managed the sale of magazines. Ebony, Jet and other magazines and newspapers for people of color were sold in barbershops and beauty parlors at the time. When I was fifteen, Jet magazine published a photograph of the lynching victim Emmet Till. That photograph changed the way I, and millions of other people around the world, thought about American justice. The photograph of the victim’s body – beaten, tortured, and bloated from days in the Mississippi River in an open casket funeral -shocked the world about the reality of American justice for African-Americans in 1955. That image introduced me to the power of the photograph.

I had daily access to the barbershop debates around Emmet Till. They were mixed and heated. Many people were angry and said it was time for a revolution. This was also the time when many of the customers were veterans of World War II and the Korean conflict. Many suffered from being “shell shocked” (now known as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder). As their condition was usually left undiagnosed and untreated, some drank constantly to escape the memories of war. Because we were taught never to look down on anyone, I listened respectfully to these veterans and everyone else’s discussions around war and civil rights. Barbershop debates are filled with a history that is very different than what is taught in the official public school system. It was this history that had space for me. My work creates this historical space for me and those like me.

“Let your vision be world-embracing, rather than confined to your own self.”

Baha’u’llah

Mastery

Mastery of one’s pursuits was very important to my father and our family. He was a master barber who was proud that he could cut many types of hair and that his razor was sharp enough to cut the toughest beard. Barbers at that time were proud of their razors so the first thing for me to learn working in his shop was how to sharpen one. When I wasn’t actually cutting hair, sweeping up, or selling the shop’s magazines, I was expected to sharpen my razor and those of the other barbers in the shop. He would check my razors and then award me a shake of the head or a half smile. I could surpass the other barbers but my work was being compared to his. While I never mastered sharpening a razor, I never gave up wanting to master what I chose to do.

It seemed like many years, but it was only a few, before I found what I really wanted to master. Photography and I met for the second time when I was nineteen in the Air Force. The first time was when I watched my siblings process film and make prints in an improvised basement darkroom in our home. I was too young to join them but I found an old camera somewhere and carried it with me pretending to take pictures. No film. No film processing. But, I imagined the three dimensional world that I lived in being flattened into a two dimensional, black and white world of stopped time.

My early love of photography became a reality in the Air Force. The small military pay was matched with a base exchange that provided cheap film, a35mm camera, and a darkroom. I’d like to say that my first real experience with photography was spectacular and recognized as being an important photographic contribution. However, my first attempts were filled with failure. When I look back at those failures, I realize that they created my desire to master this art. Being so challenged led me to look at images and try to understand the photographers’ reasons for making them.

Most photographs looked like nothing that I wanted to make as they seemed to be just pictures of things - sometimes pretty things, but still things. While writers spoke of the greatness of the photographs published in the monthly magazines, I didn’t see many images that held my interest: pieces of coiled up rope, cute pictures of children and animals, sexy pictures of women. What was photographed - the subject matter - seemed to be much more important than the photographic form. The content of the photograph seemed to be an excuse for the existence of the photograph. But, being honest with myself, I knew that my images were no better. Not only were my images just pretty pictures of things, but they also lacked evidence of technical skill. Mastering form and printing seemed to be the artistic tool that mattered. So, I began to study the capabilities and qualities of light sensitive materials. Reading textbooks about the chemistry of photography inspired me and I read them like many people read novels.

Artistic Influences

Being in the Air Force in 1965 allowed me to live in France and spend a great deal of time in the museums of Paris. I spent many hours walking the halls of The Louvre and discovered the Rodin Museum. I actually felt the muscle structure of Rodin’s sculptures and encountered “La Defense” in the middle of the Verdun Street intersection. It’s eloquence and strength almost moved me to tears. I saw art in small city museums dedicated to artists who lived in those regions. Art was part of the French cityscape and the lives of its rural citizens. Surprisingly, I could talk about the lives of artists and philosophers with the country farmers as well as intellectuals in Paris. Art was an integral part of daily life for everyone.

While stationed in Paris, and later San Francisco, I frequented museums and would often go alone to Classical music concerts and Jazz clubs. I was undergoing a process of accepting and rejecting artists. Those that moved me became part of my soul: Ornette Coleman, Bernard Malamud, Jimmy Reed, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, John Coltrane, James Brown, James Baldwin, Auguste Rodin, Vincent van Gough, and Beauford Delaney. They entered my heart and their messages spoke to me.

Strangely enough I had difficulty finding the equivalent in photography. Perhaps the problem was that I knew so much more about my art than theirs. In my mind, I knew what touched my soul and what didn’t in the art of photography. The broadest access that I had to photographs was through magazines. While Look and Life magazines had photo-stories and newspapers certainly had plenty of photographs, the images were just documents and records of events to me. And, photographs that focused on photography as an art, like many contemporary images, seemed to emphasize only technical excellence. They did not move me like Jazz or Rodin.

In 1966 while stationed in France, I purchased a copy of Camera magazine. It featured the recipients of fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Roy DeCarava and Robert Frank were two photographers included in that group and their images utterly trapped me. Both seemed to defy technical norms. DeCarava’s prints had a short tonal range that was often described as flat. Despite the tonal range of his prints, they had a luminance that should not have existed. DeCarava’s book “The Sweet Flypaper of Life” introduced me to his subject matter - the African-American community in Harlem. I’d never seen photographs that shared the life and love of the black community. I was truly inspired by his social commentary. He shared the beauty of the inhabitants of Harlem when much of America only expressed fear of this community.

Images from Robert Frank’s book “The Americans” showed a shooting style that seemed to defy the rules of formal composition. It was as if he had reinvented photographic composition and I was completely drawn to his work. The few images in the Camera magazine I’d found were like free form Jazz. The compositions seemed improvised and new. They did not feel formal and balanced in the traditional academic sense. Most images preceding his work, and most images postdating his work, follow the traditional compositional elements established by schools of painting. Robert Frank’s compositions belonged to the school of Jimmy Reed, Beauford Delaney, Bernard Malamud and the other artists who infected my soul. His compositions were brutal and honest.

I’d heard that the established art community was upset about his political commentary on America. However, as his politics were not new or alien to me, I wasn’t shocked. What shocked and pleased me was that he used the camera like Robert Frank and no one else. His compositions demanded that the viewer share the way he felt. He found a way to convey the emotion of his convictions through the camera. Frank’s images of America weren’t pictures of things or places. They were photographs that were complete in and of themselves - the images seeming complete even if one were to remove the subject matter. Frank had mastered the message spoken in his own visual language.

Finding My Own Voice

The search to tell my story, or even to recognize that I had a story, was elusive. I had to investigate myself to discover my own sense of meaning. Not until I read Langston Hughes’ poem Note on Commercial Theatre in graduate school did I understand how to do this. I was also mature enough and old enough to recognize its importance. I was 42 years old when I started college and 47 when I realized the importance of his words:

You’ve taken my blues and gone---

You sing ‘em on Broadway

And you sing ‘em in Hollywood Bowl,

And you mixed ‘em up with symphonies

And you fixed ‘em, so they don’t sound like me.

Yep, you done taken my blues and gone.

You also took my spirituals and gone.

You put me in Macbeth and Carmen Jones

And all kinds of Swing Mikados

And in everything but what’s about me---

But someday somebody’ll Stand up and talk about me,

And write about me--- Black and beautiful---

And sing about me, And put on plays about me!

I reckon it’ll be Me myself!

The line “But someday somebody’ll stand up and talk about me” is what was shared by all of the artists who had inspired me. They shared themselves - their stories, their lives, their struggles, and their triumphs. I asked myself “Who am I?” And, for the first time, my work began to search for ways to answer that honestly:

I am an African-American male living in America.

Working as a newspaper photographer for __ years after leaving the Air Force, I became aware of and frustrated by the depictions of African American men in the media. Most of the photographs of African American men published in the newspaper depicted these men as criminals and marginal to society. As an African American man myself, I did not see my story included in the cultural dialogue.

Then, because of the climate of multi-culturalism of the 1990’s, I was encouraged to make work about “my experience,” which others meant to be the African American experience. While I did not want to be confined by this definition, I realized that I did have a story to tell from that perspective and that audiences had recently opened to having that conversation. My work, therefore, focused on faces of African American men – a group whose stories had not been told. I was in a unique position to develop my own mode of communication through my personal story, the experiences of these men, and the politics involved.

Dust Shaped Hearts

"The subject matter of art is life, life as it actually is; but the function of art is to make life better." George Santayana

Dust Shaped Hearts began in 1993 with the purpose of recording the faces of African American men for posterity. The project was intended to be a sardonic statement about current news reports of the threatened “extinction of the African American male.” Drawing upon my experience as a photojournalist, I re-defined the “newspaper headshot,” in order to go beyond stereotype and give thoughtful attention and permanence to the men I photographed.

Expanding the scope of these portraits, I now photograph the human face (male and female, black, white and otherwise), not because the person possesses a dramatic “photographic” face, but because of the person’s character. I photograph writers, artists, judges, musicians, and others. The face is shaped in the darkroom process as I expose and scrub the prints until they convey an authenticity and power. The scale of the prints is large in order to allow the visual language of the materials to be seen and felt. Due to the specificity of each person and my non-reproducible printing method, only one unique print is made of each subject. Each face demands its own solution.

After researching light sensitive processes, I chose to modify a 19thcentury casein and pigment process settling on this form because it is more archival than the standard rare metal prints. Using materials as metaphor for the male and female, Dust Shaped Heartsis printed using earth (pigment) and milk (casein). Combining these organic materials to make images parallels my observation that basic photography is biological, not mechanical. In printing, I try to bring the materials together to make them one: the image, casein, and pigment become paper and the paper becomes pigment, casein, and image. Created in this manner, each print communicates the honesty and sadness of a great Blues performance.

My current work speaks to the universal human struggle against intolerance and stereotype. Melding the subject matter of the human face with a lyrical and organic printing process allows me to make prints that investigate history, humanity, and beauty. I try to create an undeniable experience of empathy in the viewer. When invited into the struggle and pain of each individual, I hope one sees him or herself in each print. A believer in unity through diversity, I create singular images that tap into the universal evolution of our humanity. Our collective sorrows and passions are the content I continue to try to master.